Well, I did it, and here’s what I learned.

First, a little background. I should note that I am a social scientist studying how innovation is understood to contribute to development in Guyana. My research consisted of expert interviews and participant observation. Someone studying, say, the mating habits of anteaters would probably have a different experience.

I chose Guyana as the site for my Ph.D. research without ever having visited the country. I knew this was a risk. There were many unknowns: Would I be able to afford a research trip to the country? Would people be willing to talk with me? How would I, a white American Ph.D. student, be received; would I be able to gain people’s trust? What would it take to do my research ethically, in a way that benefitted the communities I wanted to work with?

But I felt that the risk was worth it for two reasons. First, I had been lucky enough to become friends with a handful of Guyanese, and I had found them to be universally friendly, helpful, and supportive. Second, I knew that what was happening in Guyana was worth exploring. The country’s new-found oil wealth is poised to super-charge the country’s development trajectory, with implications not just for the 800,000 people who live in this small country, but for the world. In trying to balance an acute awareness of the dangers that come with climate change – most of the population lives under sea level – and a practical understanding of what oil makes possible, the country is plotting a peculiar development trajectory, one which may provide a model for other countries in similar situations.

Having spent nearly a month in the field, I can say now that Guyana was a wonderful place to do my research. But it is not without challenges, which any aspiring researcher should consider.

First, the benefits:

A large benefit for someone coming from the US is that Guyanese speak excellent English. Most people probably already know this, but it’s worth noting just how close American and Guyanese English actually are (I suppose it’s closer to British English, but that’s beside the point). Many times, I have met English speakers who I simply could not understand, despite our shared language. I had no problem understanding the Guyanese.

Many of the people I spoke with noted to me that they were speaking in precise English because they were talking to me, and if they were speaking with another Guyanese they would instead be utilizing the local Guyanese Creole. After a few weeks of listening to people, I found the Creole I heard to be fairly easy to understand – and full of poetry. If someone I was interviewing started including bits of Creole into our conversations, I knew that they were comfortable with me – and that the interview would be a good one.

Another benefit – especially if your research involves expert interviews – is that the country’s population is concentrated along the coast, mainly in Georgetown. This means you don’t actually have to travel very much to access a fairly large chunk of the population. Georgetown is easy to get around in taxis or mini-busses if you are adventurous.

Third, it’s worth noting that there are actually a whole bunch of foreigners in and around Georgetown nowadays. Many of them seem to be associated with the oil industry, and perhaps due to the tensions of their business, I found them to be pretty standoffish. But I also ran into journalists, other Ph.D. students, and even the odd traveler. They were all too friendly and helpful. A place called Oasis Café serves as something of a hub among the expat community – I was able to make a couple of friends and contacts just by hanging out there.

Just as friendly as the foreigners are the locals, though it is harder to make their acquaintance (see below). I was told that “once they know you, people will want to help you,” and I found that to be very true. Keep an eye out for opportunities to help people and share your knowledge and skills, and make a good impression – for example, I presented at a local small business association meeting. The Guyanese are a welcoming, supportive bunch.

Me snapping the Christianburg Waterwheel in Linden, Region 10.

Now some challenges:

The flipside of most people living along the coast is that if for some reason, you need to venture into the interior, the logistics of your trip become much more complex. I did not do this myself, but it is important to note in case some readers are considering it. If you want to do this, then you can read this article that explains the options to travel from Georgetown to Lethem.

Another challenge to doing research in Guyana – especially for cash-strapped students – is cost. Overall, things in Guyana are comparably priced to things in the USA. A taxi ride costs about what a Lyft ride might in the states. Food is perhaps a little cheaper, but not by much. And if you happen to need something that is imported – say, a coffeemaker, a pair of headphones, or a computer – you’re in trouble. These things are liable to cost more in Guyana than they would in the states. If you want a real shock, ask a Guyanese what it costs to import a car.

Scheduling in Guyana works differently than it does in the US. It is almost expected that people will be late. It is also very hard to plan things more than a day or two in advance. When I would ask someone, “are you available on Tuesday?” a common response would be “ask me on Monday.” This terrified me when I started my research (“I’m flying out tomorrow and I only have 3 scheduled interviews!”), but I came to appreciate the flexibility and people’s willingness to adapt and go with the flow. It’s easy to pick up the local rhythm with a little bit of time.

Perhaps the biggest challenge an outside researcher might face, however, is the fact that Guyana is very relationship- dependent. If people know you, they will help you out. But if they don’t know you, you’re not going to get anywhere. In the US, we might assume that reaching out with a compelling request might be enough to get a little bit of someone’s time. But this is not the case in Guyana. There were people to whom I had reached out several times and never received a response. But once I had someone introduce me, they opened up and gave me everything I needed and more. I recall one interview with a particularly suspicious respondent: he refused to sign my consent form and started the interview grilling me, trying to sus out any hidden agenda. But once we talked a bit and got to know each other, he opened up. We went on to have a 2-hour interview, after which he offered to let me borrow his motorcycle and promised to take me to a run shop the next day.

This is especially important to keep in mind when planning a research study in Guyana. You need to invest time in building your network because that is how you are going to find your respondents. If you’re planning on sampling a statistically significant segment of the population – good luck. And if you’re telling your review board that you’re going to recruit people via a form email, you definitely want to rethink that. Before I arrived in Guyana, I had sent out at least two dozen emails containing a carefully tailored recruitment script. I received exactly three responses and one of which came a whole month later. But nearly everyone whom I was introduced to was willing to meet me – sometimes that same day!

If you’re thinking about conducting research in Guyana, go for it! The country is welcoming and fascinating. But understand that conducting research in Guyana requires time, social capital, and an ability to adapt on the fly. Remember, the best we can hope for as a foreign researcher is to be a welcomed guest in Guyana. Work hard to maintain that welcome, and you’ll be fine.

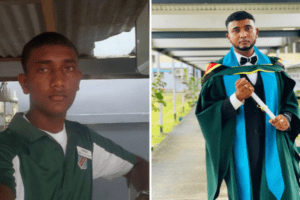

This picture was taken during my visit to Linden.

Article Written by Christopher Barton.